Bletchley Park

| Bletchley Park Museum | |

|---|---|

During World War II, codebreakers at Bletchley Park decrypted and interpreted messages from a large number of Axis code and cipher systems, including the German Enigma machine. For this purpose, the Bletchley Park mansion, pictured here, was soon joined by a host of other buildings. The mansion's façade is an idiosyncratic mix of architectural styles. |

|

| Established | 13 February 1992 |

| Location | Bletchley, Milton Keynes, England |

| Director | Simon Greenish |

| Website | www.bletchleypark.org |

Bletchley Park, also known as Station X, is an estate located in the town of Bletchley, in Buckinghamshire, England. During World War II, Bletchley Park was the site of the United Kingdom's main decryption establishment, the Government Code and Cypher School. Ciphers and codes of several Axis countries were decrypted there, most importantly ciphers generated by the German Enigma and Lorenz machines.

The high-level intelligence produced at Bletchley Park, codenamed Ultra, provided crucial assistance to the Allied war effort and is credited with having shortened the war by two years, so saving many lives [1]. However, Ultra's precise influence is still studied and debated.

Bletchley Park is now a museum run by the Bletchley Park Trust and is open to the public. The main manor house is also available for functions and is licensed for ceremonies. Part of the fees for hiring the facilities goes to the Trust for use in maintaining the museum. Since 1967, Bletchley has been part of Milton Keynes.

Contents |

Early history

The lands of the Bletchley Park estate were formerly part of the Manor of Eaton, included in the Domesday Book in 1086. Browne Willis built a mansion in 1711, but this was pulled down by Thomas Harrison, who had acquired the property in 1793. The estate was first known as Bletchley Park during the ownership of Samuel Lipscomb Seckham, who purchased it in 1877. The estate was sold on 4 June 1883 to Sir Herbert Samuel Leon (1850–1926), a financier and Liberal MP. Leon expanded the existing farmhouse into the present mansion.[2]

The architectural style is a mixture of Victorian Gothic, Tudor and Dutch Baroque and was the subject of much bemused comment from those who worked there, or visited, during World War II. Leon's estate covered 581 acres (235 hectares), of which Bletchley Park occupied about 55 acres (22 ha). Leon's wife, Fanny, died in 1937,[3] and in 1938 the site was sold to a builder, who planned to demolish the mansion and build a housing estate. Before the demolition could take place, Admiral Sir Hugh Sinclair (Director of Naval Intelligence, head of MI6, and founder of the Government Code and Cypher School) bought the site with his own money (£7,500), having failed to persuade any government department to pay for it.[4] The fact that Sinclair, and not the Government, owned the site was not widely known until 1991, when it was nearly sold for redevelopment.

To cover their real purpose, the first government visitors to Bletchley Park described themselves as "Captain Ridley's shooting party".

The estate was conveniently located within easy walking distance of Bletchley station, where the "Varsity Line" between the cities of Oxford and Cambridge – whose universities supplied many of the code-breakers – met the (then-LMSR) main West Coast railway line between London and Birmingham, Manchester, Glasgow. Starting in 1938, Post Office Telephones laid dedicated cables, for numerous telephone and telegraph circuits, from the nearby repeater station at Fenny Stratford (on Watling Street, the main road linking London to the north-west, later to be designated the A5).

Wartime history

Five weeks before the outbreak of World War II, in Warsaw, Poland's Biuro Szyfrów (Cipher Bureau) revealed its achievements in decrypting German Enigma ciphers to French and British intelligence. The British used this information as the foundation for their own early efforts to decrypt Enigma.

The "first wave" of the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) moved to Bletchley Park on 15 August 1939. The main body of GC&CS, including its Naval, Military and Air Sections, was on the house's ground floor, together with a telephone exchange, a teleprinter room, a kitchen and a dining room. The top floor was allocated to MI6. The prefabricated wooden huts were still being erected, and initially the entire "shooting party" was crowded into the existing house, its stables and cottages. These were too small, so Elmers School, a neighbouring boys' boarding school, was acquired for the Commercial and Diplomatic Sections. [5]

A wireless room was set up in the mansion's water tower and given the code name "Station X", [6] a term now sometimes applied to the codebreaking efforts at Bletchley as a whole. The "X" denotes the Roman numeral "ten", as this was the tenth such station to be opened. Due to the long radio aerials stretching from the wireless room, the radio station was moved from Bletchley Park to nearby Whaddon to avoid drawing attention to the site.[7] [8]

Listening stations – the Y-stations (such as the ones at Chicksands in Bedfordshire and Beaumanor Hall in Leicestershire, the War Office "Y" Group HQ) – gathered raw signals for processing at Bletchley. Coded messages were taken down by hand and sent to Bletchley on paper by motorcycle couriers or, later, by teleprinter. Bletchley Park is mainly remembered for breaking messages enciphered on the German Enigma cypher machine, but its greatest cryptographic achievement may have been the breaking of the German "Fish" High Command teleprinter cyphers.

The intelligence produced from decrypts at Bletchley was code-named "Ultra". It contributed greatly to Allied success in defeating the U-boats in the Battle of the Atlantic, and to the British naval victories in the Battle of Cape Matapan and the Battle of North Cape. In 1941, Ultra exerted a powerful effect on the North African desert campaign, against the German army, under General Rommel. General Auchinleck stated that, but for Ultra - "Rommel would have certainly got through to Cairo". Prior to the D-Day landings, of June 1944, the Allies knew the locations of all but two of the 58 German divisions on the Western front.

When the United States joined the war, Churchill agreed with Roosevelt to pool resources. A number of American cryptographers were posted to Bletchley Park and were inducted and then integrated into the Ultra structure, being stationed in Hut 3. From May 1943 onwards there was very close cooperation between the British and American military intelligence organizations.

Conversely, the existence of Bletchley Park, and of the decrypting achievements there, was never officially shared with the Soviet Union, whose war effort would have greatly benefited from regular decrypting of German messages relating to the Eastern Front. This reflected Churchill's concern with security, and his distrust of and hostility to communism, even during the alliance imposed on him by the Nazi threat.

The only direct action that the site experienced was when three bombs, thought to have been intended for Bletchley railway station, were dropped on 20–21 November 1940. One exploded next to the despatch riders' entrance, shifting the whole of Hut 4 (the Naval Intelligence hut) two feet on its base. As the huts stood on brick pillars, workmen just winched it back into position while work continued inside.

After the war, Churchill referred to the Bletchley staff as "My geese that laid the golden eggs and never cackled".[9]

Cryptanalysis

| The Enigma cipher machine |

|---|

|

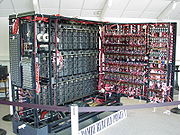

Most of the messages subjected to cryptanalysis at BP were enciphered with some variation of the Enigma cipher machine.

From 1943, Colossus, the earliest digital electronic computers, was constructed in order to break the German teleprinter on-line Lorenz cipher known as Tunny. Colossus was designed and built by Tommy Flowers and his team at the Post Office Research Station at Dollis Hill. The Colossus series of machines, of which there were ten by the end of the war, were operated at Bletchley Park in a section named the Newmanry after its head Max Newman.

Some 9,000 people were working at Bletchley Park at the height of the codebreaking efforts in January 1945,[10] and over 12,000 (of whom more than 80% were women) worked there at some point during the war.[10] A relatively small number of men were also employed on a part-time basis, typically for one shift each week (e.g. Post Office employees who were experts in Morse code or the German language). Among the famous mathematicians and cryptanalysts working there, perhaps the most influential and certainly the best-known in later years was Alan Turing. A number of Bletchley Park employees were recruited for various intellectual achievements, whether they were chess champions, crossword experts, polyglots or great mathematicians. In one, now well known instance, the ability to solve The Daily Telegraph crossword in under 12 minutes was used as a recruitment test. The newspaper was asked to organize a crossword competition, after which each of the successful participants was contacted and asked if they would be prepared to undertake "a particular type of work as a contribution to the war effort". The competition itself was won by F H W Hawes of Dagenham who finished the crossword in less than eight minutes.[11]

Japanese codes

An outpost of the Government Code and Cypher School was set up in Hong Kong in 1935, the Far East Combined Bureau (FECB). The FECB naval staff moved in 1940 to Singapore, then Colombo, Ceylon, then Kilindini, Mombasa, Kenya. They succeeded in deciphering Japanese codes with a mixture of skill and good fortune.[12] The Army and Air Force staff went from Singapore to the Wireless Experimental Centre at Delhi, India. In early 1942, a six-month crash course in Japanese, for 20 undergraduates from Oxford and Cambridge, was started by the Inter-Service Intelligence school in Bedford, in a building across from the main Post Office. This course was repeated every six months until war's end. The LMS railway provided twice-daily trains, reserved for BP workers, between Cambridge and Bletchley, stopping at Bedford St Johns railway station).

Most of those completing these courses worked on decoding Japanese naval messages in Hut 7, under Col. J. Tiltman. By mid-1945 well over 100 personnel were involved with this operation, which co-operated closely with the FECB and the US Signal intelligence Service at Arlington Hall, Virginia. Because of these joint efforts, by August 1945 the Japanese mechant navy was suffering 90% losses at sea.

In 1999, Michael Smith wrote that: Only now are the British codebreakers (like John Tiltman, Hugh Foss and Eric Nave) beginning to receive the recognition they deserve for breaking Japanese codes and cyphers.[13]

After the war

At the end of the war, much of the equipment used and its blueprints were destroyed. Although thousands of people were involved in the deciphering efforts, the participants remained silent for decades about what they had done during the war, and it was only in the 1970s that the work at Bletchley Park was revealed to the general public. After the war, the site belonged to several owners, including British Telecom, the Civil Aviation Authority[14] and PACE (Property Advisors to the Civil Estate). GCHQ (Government Communications Headquarters), the post-war successor organisation to GC&CS, ended training courses at Bletchley Park in 1987.

The local headquarters for the GPO was based here and housed all the engineers for the local area together with all the support they needed. The Eastern Region training school was also based in the park and later part of the national BT management college which was relocated here from Horwood House. There was also a teacher-training college.

By 1991, the site was nearly empty and the buildings were at risk of demolition for redevelopment. On 10 February 1992, Milton Keynes Borough Council declared most of the Park a conservation area. Three days later, on 13 February 1992, the Bletchley Park Trust was formed to maintain the site as a museum devoted to the codebreakers. The site opened to visitors in 1993, with the museum officially inaugurated by HRH the Duke of Kent, as Chief Patron, in July 1994. On 10 June 1999 the Trust concluded an agreement with the landowner, giving control over much of the site to the Trust.[15]

The Trust is volunteer-based and relies on public support to continue its efforts. Christine Large was appointed Director of the Trust in March 1998. On 1 March 2006, the Park Trust announced that Simon Greenish had been appointed Director Designate, and would work alongside Large in 2006,[16] taking over on 1 May 2006.

In October 2005, American billionaire Sidney Frank donated £500,000 to Bletchley Park Trust to fund a new Science Centre dedicated to Alan Turing.[17]

A team headed by Tony Sale has undertaken reconstruction of a Colossus computer at The National Museum of Computing, which is also located within the park.[18] Another team, led by John Harper, has undertaken a rebuild of the bombe.[19] On 6 September 2006, the Trust demonstrated[20] that the Bombe was back in action.

|

A 1:40 scale model of a German World War II U-boat, used in the film Enigma and later donated to the Bletchley Park museum.

|

A project to construct a working replica of a bombe is nearing completion.

|

Other attractions

The park is also home to a number of other organizations, both commercial and otherwise.

National Museum of Computing

In 2008 the museum signed a 25-year lease for the park's Block H to establish this national museum on the history of computing. Though separate legal entities, the two trusts work closely together.

The museum includes a reconstructed Colossus computer by a team headed by Tony Sale[21], along with many important examples of computing machinery.

Radio Society of Great Britain

In April 2008 the General Manager of the Radio Society of Great Britain announced that they were moving the Society's "public headquarters" (library, radio station, museum and bookshop) to Bletchley Park.[22] The RSGB intended to open the "RSGB Pavilion" in Bletchley Park in late summer to early autumn 2008. However the building allocated to them was beyond economical repair and they will open in a different location during April 2010.[23]

Other museum attractions

Other buildings at Bletchley Park feature additional exhibits. Some are only open on specified days.

- The mansion itself is open for tours on Sundays. It is also open on other days when it is not used for private functions.

- Rebuild of the Bombe device used to help to decrypt German Enigma machine-generated signals

- Winston Churchill Exhibit - collection of Winston Churchill memorabilia

- Projected Picture Trust - collection of vintage cinema equipment and a small theatre showing World War II-era movie shorts

- Toy & Memorabilia Collection - 1930s period toy soldiers, model trains, model vehicles, Wm. Britain's lead farm and garden, and other toys, dolls and teddy bears

- Bletchley Park Garage - cars include two 1930s Austin Motor Company autos that were used in the movie The Eagle Has Landed

- Bletchley Park Post Office - a recreation of the 1940s post office used as cover for mail delivered to the employees of Bletchley Park. The gift shop is a publisher of limited edition first day covers.

Funding needs

In May 2008 it was announced that the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation had turned down a request for funds because the foundation only funds Internet-based technology projects. Since Bletchley Park receives no external funding, it is in dire need of financial support. Simon Greenish, the Bletchley Park Trust's director said:

We are just about surviving. Money – or lack of it – is our big problem here. I think we have two to three more years of survival, but we need this time to find a solution to this.[24]

On 24 July 2008 more than a hundred academics signed a letter to The Times condemning the neglect being suffered by the site.[25][26] In September 2008, PGP, IBM and other technology firms announced a fund-raising campaign to repair the facility.[27]

On 6 November 2008 it was announced that English Heritage would donate £300,000 to help maintain the buildings at Bletchley Park, and that they were in discussions regarding the donation of a further £600,000.[28]

In July 2009, the British government announced that personnel who had worked at the park during the war would be recognized with a commemorative badge.[29]

Sue Black and others have used Twitter and other social media to raise the profile and funding for Bletchley Park.[30]

Buildings

The huts were designated by numbers; in some cases, the hut numbers became associated as much with the work which went on inside the buildings as with the buildings themselves. Because of this, when a section moved from a hut into a larger building, they were still referred to by their "Hut" code name.

Some of the hut numbers, and the associated work, are:

- Hut 1 – the first hut, built in 1939[31]

- Hut 3 – intelligence: translation and analysis of Army and Air Force Enigma decrypts

- Hut 4 – Naval intelligence: analysis of Naval Enigma decrypts

- Hut 6 – Cryptanalysis of Army and Air Force Enigma[32]

- Hut 7 – Cryptanalysis of Japanese naval codes[33][34]

- Hut 8 – Cryptanalysis of Naval Enigma

- Hut 10 – Meteorological section[35]

- Hut 11 – The first Bombe building[36]

- Hut 14 – main teleprinter building[37]

In addition to the wooden huts there were a number of brick-built blocks.

- Block A - Naval Intelligence

- Block B - Italian Air and Naval, and Japanese code breaking

- Block C - Stored the substantial punch-card index

- Block D - Enigma work, extending that in huts 3, 6 and 8

- Block E - Incoming and outgoing Radio Transmission and TypeX

- Block F - included the Newmanry and Testery. It has since been demolished.

- Block G - Traffic analysis and deception operations

- Block H - Lorenz and Colossus (now The National Museum of Computing)

In popular culture

- Bletchley featured heavily in Enigma and its 2001 film adaptation

- The WWII code breaking sitcom pilot "Satsuma & Pumpkin" was recorded at Bletchley Park in 2003 and featured the late Bob Monkhouse OBE in his last ever screen role. The BBC declined to produce the show and develop it further before creating effectively the same show on Radio 4 several years later, featuring some of the same cast, entitled Hut 33. Parts of the unseen pilot are to be shown on documentaries about Bob Monkhouse on both ITV & BBC in 2010. [38]

- The BBC Radio 4 sitcom Hut 33 is also set at Bletchley.[39]

- The ITV television serial Danger UXB featured the character Steven Mount who was a codebreaker at Bletchley, and was driven to a nervous breakdown (and eventual suicide) by the stressful and repetitive nature of the work.

- In BBC's Torchwood series, the character Toshiko Sato is revealed to have had a grandfather who worked at Bletchley Park up until the bombing of Pearl Harbor by Japan. Whether he continued working there after Japan declared war on the Allies is unknown.

- A fictionalized version of Bletchley Park is featured in the novel Cryptonomicon by Neal Stephenson.

- On 19 June 2007 a 1.5-ton, life-size statue of Alan Turing was unveiled at Bletchley Park. Built from approximately half a million pieces of Welsh slate, it was sculpted by Stephen Kettle, having been commissioned by the late American billionaire Sidney Frank.[40]

- Bletchley came to wider public attention from the 1999 documentary series Station X.[41]

See also

- List of people associated with Bletchley Park

- Newmanry

- Testery

- Y-stations

- Arlington Hall

- National Cryptologic Museum

- Danesfield House

- Beeston Regis, Norfolk Chapter on the Y Station on Beeston Bump

- Far East Combined Bureau in Hong Kong prewar, then Singapore, Colombo (Ceylon) and Kilindini (Kenya)

- Wireless Experimental Centre operated by the Intelligence Corps outside Delhi

References

- ↑ Hinsley (1993) Introduction in F. H. Hinsley & A. Stripp, Codebreakers: The Inside Story of Bletchley Park, pp. 11-13

- ↑ Edward Legg, Early History of Bletchley Park 1235–1937, Bletchley Park Trust Historic Guides series, No. 1, 1999

- ↑ Valentin Foss "Bletchley Park"

- ↑ Smith, Michael (1999) [1998]. Station X: The Codebreakers of Bletchley Park. Channel 4 Books. p. 20. ISBN 978-0752221892.

- ↑ Smith, 1998 page 2-3

- ↑ Bob Watson, "How the Bletchley Park Buildings Took Shape", Appendix in F. H. Hinsley & A. Stripp, Codebreakers: The Inside Story of Bletchley Park, 1993

- ↑ The Secrets of Bletchley Park — Souvenir Guide, Bletchley Park Trust, 2nd edition, 2003

- ↑ Pidgeon, Geoffrey (2003) [2003]. Station X — The Secret Wireless War. Universal Publishing Solutions Online Ltd. ISBN 978-1843752523.

- ↑ Douglas J. Hall, History Lives at Ditchley and Bletchley.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Smith, 1998, pp. 175-6

- ↑ The Daily Telegraph, "25000 tomorrow" 23 May 2006

- ↑ coastweek.com

- ↑ Smith, Michael and Erskine, Ralph (editors): Action this Day page 151 (2001, Bantam London; pages 127-51) ISBN 0593 049101 (Chapter 8: An Undervalued Effort: how the British broke Japan’s Codes by Michael Smith)

- ↑ BellaOnline "Britain's Best Kept Secret"

- ↑ Bletchley Park Trust "Bletchley Park History"

- ↑ Bletchley Park Trust Appoints Director Designate, Bletchley Park News, 1 March 2006

- ↑ Action This Day, Bletchley Park News, 28 February 2006

- ↑ Tony Sale "The Colossus Rebuild Project"

- ↑ John Harper "The British Bombe"

- ↑ The Guardian "Back in action at Bletchley Park, the black box that broke the Enigma code."

- ↑ Tony Sale "The Colossus Rebuild Project"

- ↑ Peter Kirby, GoTWW (May 2008). "Relocation Update". RadCom (Radio Society of Great Britain) 84 (05): 06.

- ↑ "Bletchley Park Latest". RadCom (Radio Society of Great Britain) 84 (10): 06. October 2008.

- ↑ ZDNet "Bletchley Park Faces Bleak Future"

- ↑ Letters "Saving the heritage of Bletchley Park", The Times.

- ↑ "Neglect of Bletchley condemned", BBC News.

- ↑ PGP, IBM help Bletchley Park raise funds

- ↑ "New lifeline for Bletchley Park", BBC News.

- ↑ "Enigma codebreakers to be honoured finally", The Daily Telegraph.

- ↑ Sue Black, Jonathan P. Bowen, and Kelsey Griffin, Can Twitter Save Bletchley Park? In David Bearman and Jennifer Trant (editors), MW2010: Museums and the Web 2010, Denver, USA, 13–17 April 2010. Archives & Museum Informatics.

- ↑ Tony Sale "Bletchley Park Tour", Tour 3.

- ↑ Gordon Welchman (1982). The Hut Six Story: Breaking the Enigma Codes. Allen Lane (London) & , McGraw-Hill (New York). ISBN 0713912944.

- ↑ F. H. Hinsley and Alan Stripp, eds. Codebreakers: The Inside Story of Bletchley Park, Oxford University Press, 1993

- ↑ Norman Scott, “Solving Japanese Naval Ciphers 1943 – 45”, Cryptologia, Vol 21(2), April 1997, pp149–157

- ↑ David Kahn, 1991, Seizing the Enigma, pp. 189–190

- ↑ Tony Sale "Bletchley Park Tour", Tour 4

- ↑ "Beaumanor & Garats Hay Amateur Radio Society "The operational huts"". Archived from the original on 2007-11-13. http://web.archive.org/web/20071113140236/http://beaumanor.hosted.pipemedia.net/History/operational+Huts.htm.

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ BBC Radio 4 — Comedy — Hut 33

- ↑ "Bletchley Park Unveils Statue Commemorating Alan Turing". http://www.bletchleypark.org.uk/news/docview.rhtm/454075. Retrieved 2007-06-30.

- ↑ Station X (1999) (TV)

Further reading

- Richard J. Aldrich, GCHQ: The Uncensored Story of Britain's Most Secret Intelligence Agency, HarperCollins, 2010. ISBN 9780007278473.

- Peter Calvocoressi, Top Secret Ultra, Baldwin, new edn 2001. ISBN 978-0-947712-41-9

- Ted Enever, Britain's Best Kept Secret: Ultra's Base at Bletchley Park, 3rd edition, 1999, ISBN 0-7509-2355-5.

- F. H. Hinsley and Alan Stripp, eds. Codebreakers: The Inside Story of Bletchley Park, Oxford University Press, 1993, ISBN 0-19-820327-6.

- Christine Large, Hijacking Enigma: The Insider's Tale, 2003, ISBN 0-470-86346-3.

- Hugh Sebag-Montefiore, Enigma: the Battle for the Code, London, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2000, ISBN 978-0-471-49035-7.

- Michael Smith, Station X, Channel 4 Books, 1998. ISBN 0-330-41929-3 or ISBN 0-7522-2189-2.

- Doreen Luke, My Road to Bletchley Park. Baldwin, 3rd edn 2005. ISBN 978-0-947712-44-0.

- Mick Manning, Taff in the WAAF, Janetta Otter-Barry Books (Frances Lincoln), 2010. ISBN 978-1-84780-093-0

- Sinclair McKay, The Secret Life of Bletchley Park: the WWII Codebreaking Centre and the Men and Women Who Worked There, Aurum, 2010.

- Hilton, Peter (1988). "Reminiscences of Bletchley Park, 1942–1945" (PDF). pp. 291–301. http://www.ams.org/online_bks/hmath1/hmath1-hilton22.pdf. Retrieved 2009-09-13. (CAPTCHA) (10-page preview from A Century of mathematics in America, Volume 1 By Peter L. Duren, Richard Askey, Uta C. Merzbach, see http://www.ams.org/bookstore-getitem/item=HMATH-1 ; ISBN 978-0-8218-0124-6.

- Gordon Welchman, The Hut Six Story: breaking the Enigma codes. Baldwin, new edn 1997, ISBN 978-0-947712-34-1.

- Gwen Watkins, Cracking the Luftwaffe Codes, 2006, Greenhill Books, ISBN 978-1-85367-687-1

External links

- Bletchley Park Trust

- Bletchley Park — Virtual Tour — by Tony Sale

- The National Museum of Computing (based at Bletchley Park)

- "New hope of saving Bletchley Park for nation" (Daily Telegraph 3 March 1997)

- Boffoonery! Comedy Benefit For Bletchley Park Comedians and computing professionals stage comedy show in aid of Bletchley Park

- Bletchley Park: It's No Secret, Just an Enigma, The Telegraph, 29 August 2009

- Bletchley Park is official charity of Shed Week 2010 — in recognition of the work done in the Huts

- Saving Bletchley Park blog by Sue Black

- GCHQ: Britain's Most Secret Intelligence Agency